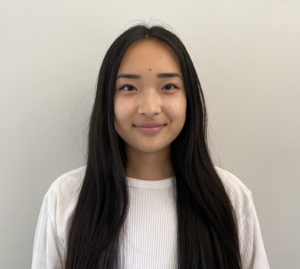

Trainee Spotlight: Katya Loban

We are thrilled to congratulate Katya Loban on her outstanding achievements! Katya will be presenting three abstracts at upcoming conferences: the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research (CAHSPR) 2023 Conference, to be held in Montreal from May 29-31, 2023, and the American Transplant Congress, to be held in San Diego from June 3-7, 2023.

At the CAHSPR conference, Katya will be giving an oral presentation on living kidney donation entitled: “Thank you for your kidney, good-bye.”: The Canadian living kidney donor perspective. At the American Transplant Congress, she will participate in an oral presentation entitled “Are We Providing Optimal Care, Information, and Support to Living Kidney Donors? A Qualitative Study.” In addition, Katya will present a poster on “What I Desire from My Family Physician: The Living Kidney Donor Perspective.“

These presentations at such prestigious conferences are a testament to Katya’s hard work, dedication, and expertise in the field of healthcare. We applaud her achievements and look forward to hearing the valuable insights she will undoubtedly contribute.

Congratulations, Katya!

About Katya Loban

Katya Loban is a health services researcher. She is a postdoctoral fellow at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre and the Department of Medicine of McGill University, working under the supervision of Dr. Shaifali Sandal. Katya is also a trainee with the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program (CDTRP). Katya holds a PhD in Family Medicine and Primary Care, an LLM in International Dispute Resolution and an MA in Organization Development. She has 14 years of professional experience in the areas of international project management and research administration. Katya’s areas of interest include multi-stakeholder partnerships, inter-professional collaboration, the organizational aspects of health care and medical law and ethics. The aim of her current postdoctoral project is to explore the integration of primary care into the living donation trajectory, to optimize the care of living kidney donors.

Abstract for the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research (CAHSPR) 2023 Conference

“Thank you for your kidney, good-bye.”: The Canadian living kidney donor perspective

K. Loban, J-T. Robert, P. Nugus, C. Rodriguez, S. Sandal

Background and objectives: Living donor kidney transplantation saves the Canadian healthcare system millions of dollars in averted dialysis costs, is the best treatment for kidney failure, and helps to narrow the persistent gap between the demand and supply of organs. Evidence suggests that this process is fraught with challenges for living kidney donors (LKDs). We aimed to obtain the perspectives of LKDs on their healthcare throughout the donation trajectory, with a focus on the role of primary care.

Approach: This was a qualitative descriptive study, entailing 49 semi-structured interviews with LKDs. Adult male and female participants who spoke English or French and donated their kidney to someone they knew or anyone in need prior to 2020 were recruited via social media and email rosters from seven transplant jurisdictions in Canada. Interviews were conducted in person or via zoom. Interview questions related to perceived gaps in the provision of information on donation, experiences pre- and post-donation and the coordination of care among different healthcare providers. Data were analyzed using inductive content analysis.

Results: LKD care lies at the intersection of primary and transplant care. Our analysis revealed: 1) variability in health information provision, 2) poor coordination between levels of care, and 3) gaps in post-donation care accessibility and comprehensiveness. Post-donation, most donors were under the care of their family physicians, some had limited annual follow-ups with transplant teams, and a minority of donors lacked access to care altogether. Many donors felt abandoned by the transplant teams. Those LKDs who felt “healthy” perceived follow-up by family physicians as acceptable, although many noted significant gaps in the knowledge of family physicians regarding LKD care. A key challenge identified was a lack of ongoing support for mental health

Conclusion: This study suggests that in Canada, a country with universal health care, LKDs have unmet needs. Its results underscore the need for stronger integrative models of primary and tertiary care, with the living donor at their core. In addition, targeted medical education initiatives for primary care practitioners are needed.

Abstracts for the American Transplant Congress

Are we providing optimal care, information, and support to living kidney donors? A qualitative study

K. Loban, J-T. Robert, H. Badenoch, A. Bugeja, P. Nugus, C. Rodriguez, S. Sandal

Purpose: Living kidney donors (LKDs) experience several challenges when pursuing donation and their follow-up care is suboptimal. Data from the US have demonstrated that many centers are not in compliance with the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing mandated follow-up of LKDs and that lack of health insurance may play a role. Thus, we wanted to explore the experiences and needs of LKDs in Canada as they transition through the five phases of their donation trajectory.

Methods: This was a pan-Canadian qualitative descriptive study, entailing 49 semi-structured interviews with LKDs who were recruited via social media or email rosters. Data were analyzed using inductive thematic analysis.

Results: Participants reported: 1) unmet health information needs prior to donation, 2) poor coordination and lack of continuity between primary care and transplant teams, 3) inconsistency in post-donation care protocols, 4) challenges with access to care post-donation, and 5) suboptimal long-term follow-up. Post-donation most donors were under the care of their family physicians, some had annual follow-ups with transplant teams exclusively for monitoring remaining kidney function, and a minority of donors lacked access to care altogether. Many donors often felt abandoned by the transplant teams post-donation, particularly in light of very intense screening and evaluation leading to surgery. Those LKDs who felt “healthy” perceived follow-up by family physicians as acceptable, although many noted significant gaps in the knowledge of family physicians regarding donor care. A key challenge identified by nearly all donors was a lack of ongoing support for mental health.

Conclusions: We report that even in a country with universal health care, LKDs have unmet needs. Our data can inform targeted multi-disciplinary interventions to improve care coordination, facilitate early detection of problem symptoms and enhance the experiences of LKDs which would, ultimately, lead to better short- and long-term patient outcomes.

“What I desire from my family physician”: the living kidney donor perspective

K. Loban, J-T. Robert, H. Badenoch, P. Nugus, C. Rodriguez, S. Sandal

Purpose: In the US, transplant centers are mandated by the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) to follow living kidney donors (LKDs) for two years after donation, yet a majority of LKDs are lost to follow-up. LKDs are healthy individuals whose main health care contact prior to and after donation are primary care practitioners, such as family physicians (FPs). Better engagement of FPs can inform improved compliance with the OPTN policy as well as optimal long-term care of LKDs. We aimed to obtain the perspectives of LKDs on the role of FPs pre- and post-donation.

Methods: This was a pan-Canadian qualitative descriptive study that aimed to obtain the perspectives of LKDs. We chose Canada as the setting for this study as lack of insurance is not a major barrier to access care. We conducted 49 semi-structured interviews with LKDs who were recruited via social media or email rosters. Data were analyzed using thematic analysis.

Results: Having a FP was a prerequisite for being a LKD for most transplant programs. Post-donation, most LKDs were under the care of their FPs. In practice, the role of FPs was confined to occasional pre-donation physical screening and limited long-term follow-up. Participants reported poor coordination between primary and transplant care and significant gaps in the knowledge of FPs regarding living donation and long-term donor care. A few stated that their FPs implicitly or explicitly discouraged donation. Desired roles for FPs included health information brokerage, mental health support and long-term kidney function monitoring. Some illustrative quotes are highlighted in Table 1.

Conclusions: We have identified several opportunities for improving long-term donor follow-up and care much beyond the two-year mandate from the OPTN. Given that LKDs are generally under the care of a FP pre- and post-donation, targeted medical education initiatives and stronger integrative models of primary and tertiary care are needed.

ity of Alberta and has received training in patient-oriented research through the University of Calgary’s PACER (Patient and Community Engagement Research) Program. He is the Patient, Family, and Donor Partnerships & Education Manager with the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program. In this role, Manuel builds relationships patient partners with investigators and strengthens capacity among CDTRP patient partners.

ity of Alberta and has received training in patient-oriented research through the University of Calgary’s PACER (Patient and Community Engagement Research) Program. He is the Patient, Family, and Donor Partnerships & Education Manager with the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program. In this role, Manuel builds relationships patient partners with investigators and strengthens capacity among CDTRP patient partners.

Anders Billström

Anders Billström  Gareth Wiltshire

Gareth Wiltshire

K

K

Sherrie Logan

Sherrie Logan

born and raised in Edmonton, AB. With a degree in Music Performance (saxophone performance) and Education, Lindsey has taught for over a decade in the Edmonton Public School system. When she is not teaching, she is very involved in the music community, performing in the Edmonton Winds, conducting her own community ensemble (The Beer League Band) and on numerous musical boards across the province. For the past 5 years, Lindsey has had to take a break from teaching after having her amazing son, George. Maternity leave did not goes as expected as George was diagnosed with Dilated Cardiomyopathy at 5 months old and required 2 heart transplants before the age of 4. During this time, Lindsey has also began to dedicate her time building and expanding her charity: Big Gifts for Little Lives, where they raise money to fund Pediatric Heart Transplant research at the Stollery.

born and raised in Edmonton, AB. With a degree in Music Performance (saxophone performance) and Education, Lindsey has taught for over a decade in the Edmonton Public School system. When she is not teaching, she is very involved in the music community, performing in the Edmonton Winds, conducting her own community ensemble (The Beer League Band) and on numerous musical boards across the province. For the past 5 years, Lindsey has had to take a break from teaching after having her amazing son, George. Maternity leave did not goes as expected as George was diagnosed with Dilated Cardiomyopathy at 5 months old and required 2 heart transplants before the age of 4. During this time, Lindsey has also began to dedicate her time building and expanding her charity: Big Gifts for Little Lives, where they raise money to fund Pediatric Heart Transplant research at the Stollery.

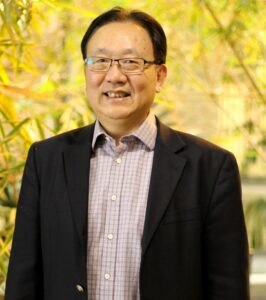

Dr. Caigan Du is a scientist at the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute and an assistant professor in the Department of Urologic Sciences at the University of British Columbia. He received a Ph.D. degree in Biochemistry in UK and postdoctoral training in Immunology in USA. He is interested in the pathogenesis of kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury and transplant rejection, and molecular control of urinary malignancies. He has been studying the impact of kidney donor-derived factors on renal allograft rejection, and the molecular pathways of kidney injury and regeneration in experimental models. He is also interested in developing medical solution including drugs made from natural compounds for all kinds of health problems, including immune disorders, organ preservation, kidney failure and urinary cancer. He is the PI of many grant supports from the Kidney Foundation of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Dr. Caigan Du is a scientist at the Vancouver Coastal Health Research Institute and an assistant professor in the Department of Urologic Sciences at the University of British Columbia. He received a Ph.D. degree in Biochemistry in UK and postdoctoral training in Immunology in USA. He is interested in the pathogenesis of kidney ischemia-reperfusion injury and transplant rejection, and molecular control of urinary malignancies. He has been studying the impact of kidney donor-derived factors on renal allograft rejection, and the molecular pathways of kidney injury and regeneration in experimental models. He is also interested in developing medical solution including drugs made from natural compounds for all kinds of health problems, including immune disorders, organ preservation, kidney failure and urinary cancer. He is the PI of many grant supports from the Kidney Foundation of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Heather Badenoch is a non-directed living liver donor and communications strategist. As the president of Village PR, she provides strategic communications direction and training to not-for-profit clients in community and health. An active transplant volunteer, Heather helps transplant candidates find living donors by running their public appeals, small and large, pro-bono. She also mentors potential living donors on the path to living donation. Heather is a volunteer with the UHN Centre for Living Organ Donation and the Canadian Donation and Transplant Research Program. She and her spouse adopt rescue dogs and volunteer together with Community Veterinary Outreach, a group providing free veterinary care to the pets of people who are homeless.

Heather Badenoch is a non-directed living liver donor and communications strategist. As the president of Village PR, she provides strategic communications direction and training to not-for-profit clients in community and health. An active transplant volunteer, Heather helps transplant candidates find living donors by running their public appeals, small and large, pro-bono. She also mentors potential living donors on the path to living donation. Heather is a volunteer with the UHN Centre for Living Organ Donation and the Canadian Donation and Transplant Research Program. She and her spouse adopt rescue dogs and volunteer together with Community Veterinary Outreach, a group providing free veterinary care to the pets of people who are homeless.

Sean Dicks is a clinical psychologist who has 20 years’ experience supporting both families of organ donors and transplant recipients. While it is rare for him to have contact with a donor family and recipient linked to the same organ donation-transplantation event, his contact with families who have lived experience with organ donation on the one hand, and patients who have received transplants on the other hand has provided opportunities to explore how their journeys become linked when they attempt to make sense of and find meaning in their respective crises.

Sean Dicks is a clinical psychologist who has 20 years’ experience supporting both families of organ donors and transplant recipients. While it is rare for him to have contact with a donor family and recipient linked to the same organ donation-transplantation event, his contact with families who have lived experience with organ donation on the one hand, and patients who have received transplants on the other hand has provided opportunities to explore how their journeys become linked when they attempt to make sense of and find meaning in their respective crises.

Terri Hansen-Gardiner is a Cree speaking Metis woman from Northern Saskatchewan as well as a 10 year Breast Cancer Survivor. Her tireless spirit and dedication to her community is undeniable. Terri is a cancer survivor who travels around the province to provide assistance, information, and support to Indigenous patients who are trying to access and navigate the cancer care system.

Terri Hansen-Gardiner is a Cree speaking Metis woman from Northern Saskatchewan as well as a 10 year Breast Cancer Survivor. Her tireless spirit and dedication to her community is undeniable. Terri is a cancer survivor who travels around the province to provide assistance, information, and support to Indigenous patients who are trying to access and navigate the cancer care system.

Dr. Golnaz Karoubi is Assistant Scientist at the Toronto General HospitalResearch Institute and principal investigator in the Latner Thoracic Research Labs. She currently holds an Assistant Professor appointment in the department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology and a cross-appointment in the department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at the University of Toronto. Dr. Karoubi received her PhD in Applied Science and Engineering at the University of Toronto and joined the Lung Regenerative Medicine Program in the Department of Clinical Research in Berne University, Switzerland for a post-doctoral research fellowship. She stayed on as a Group Leader in 2008 to direct the basic and transitional science as related to Cancer Stem Cell and Lung Regenerative Medicine in the Department of Biomedical Research at the University of Berne until 2012. In early 2012, she joined the team of Dr. Tom Waddell at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute as a Senior Scientific Associate and was appointed to Assistant Scientist at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute (University Health Network) in November 2019 and to Assistant Professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology in July 2020.

Dr. Golnaz Karoubi is Assistant Scientist at the Toronto General HospitalResearch Institute and principal investigator in the Latner Thoracic Research Labs. She currently holds an Assistant Professor appointment in the department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology and a cross-appointment in the department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at the University of Toronto. Dr. Karoubi received her PhD in Applied Science and Engineering at the University of Toronto and joined the Lung Regenerative Medicine Program in the Department of Clinical Research in Berne University, Switzerland for a post-doctoral research fellowship. She stayed on as a Group Leader in 2008 to direct the basic and transitional science as related to Cancer Stem Cell and Lung Regenerative Medicine in the Department of Biomedical Research at the University of Berne until 2012. In early 2012, she joined the team of Dr. Tom Waddell at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute as a Senior Scientific Associate and was appointed to Assistant Scientist at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute (University Health Network) in November 2019 and to Assistant Professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology in July 2020. Dr. Haykal graduated from the University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine in2007 as class valedictorian and silver medalist, and subsequently completed her residency training in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Toronto in 2016. During her residency, she completed a four-year Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine and immunology with a focus on tracheal reconstruction. She obtained numerous grants and awards including a CIHR Vanier Scholarship. Dr. Haykal then pursued fellowship training in microsurgical reconstruction at the Albany Medical Centre in New York. Dr. Haykal joined the University Health Network and the Toronto General Hospital in 2018. Her clinical focus is on complex oncological reconstruction and microsurgical reconstruction of the breast, head and neck and extremity. She started a lymphedema program in 2019 where she offers microsurgical techniques for the treatment of lymphedema.

Dr. Haykal graduated from the University of Ottawa Faculty of Medicine in2007 as class valedictorian and silver medalist, and subsequently completed her residency training in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at the University of Toronto in 2016. During her residency, she completed a four-year Doctorate of Philosophy (PhD) in tissue engineering, regenerative medicine and immunology with a focus on tracheal reconstruction. She obtained numerous grants and awards including a CIHR Vanier Scholarship. Dr. Haykal then pursued fellowship training in microsurgical reconstruction at the Albany Medical Centre in New York. Dr. Haykal joined the University Health Network and the Toronto General Hospital in 2018. Her clinical focus is on complex oncological reconstruction and microsurgical reconstruction of the breast, head and neck and extremity. She started a lymphedema program in 2019 where she offers microsurgical techniques for the treatment of lymphedema. Dr. Ahmed is a Professor in the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary. The recipient of the 2022 Hypertension Canada Senior Investigator Award, she is a nephrologist and clinician-scientist with a focus on sex and gender differences in human cardiovascular/kidney physiology and clinical outcomes. Dr. Ahmed is the Vice Chair (Research) for the Department of Medicine, Lead of the Libin Institute Women’s Cardiovascular Health Research Initiative at the University of Calgary and Lead of the Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Capacity Development Platform. Dr. Ahmed is an Advisory Board member for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Gender and Health, a member of the Canadian Medical Association Journal Governing Council and the President-Elect for the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences.

Dr. Ahmed is a Professor in the Cumming School of Medicine at the University of Calgary. The recipient of the 2022 Hypertension Canada Senior Investigator Award, she is a nephrologist and clinician-scientist with a focus on sex and gender differences in human cardiovascular/kidney physiology and clinical outcomes. Dr. Ahmed is the Vice Chair (Research) for the Department of Medicine, Lead of the Libin Institute Women’s Cardiovascular Health Research Initiative at the University of Calgary and Lead of the Alberta Strategy for Patient Oriented Research Capacity Development Platform. Dr. Ahmed is an Advisory Board member for the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Institute of Gender and Health, a member of the Canadian Medical Association Journal Governing Council and the President-Elect for the Organization for the Study of Sex Differences.

r. Christopher Nguan is an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia in the Department of Urological Sciences, Surgical Head of Kidney Transplantation at Vancouver General Hospital and the Director of the Surgical Technologies Experimental Laboratory & Advanced Robotics (STELLAR) facility at Vancouver General Hospital.

r. Christopher Nguan is an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia in the Department of Urological Sciences, Surgical Head of Kidney Transplantation at Vancouver General Hospital and the Director of the Surgical Technologies Experimental Laboratory & Advanced Robotics (STELLAR) facility at Vancouver General Hospital. r Caroline Lamarche is a clinician scientist and transplant nephrologist at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital. She is an assistant clinical professor at the Université de Montréal. After her nephrology training at the Université de Montréal (2015), she completed a Master degree on the use of adoptive immunotherapy to treat/prevent BK nephropathy in kidney transplant recipients. She then pursued a post-doctoral fellowship with Dr. Megan Levings at the University of British Columbia on the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) regulatory T cells (Tregs) to induce transplant tolerance. Her lab is working on the development of adoptive immunotherapy in nephrology and understanding Treg dysfunction.

r Caroline Lamarche is a clinician scientist and transplant nephrologist at Maisonneuve-Rosemont Hospital. She is an assistant clinical professor at the Université de Montréal. After her nephrology training at the Université de Montréal (2015), she completed a Master degree on the use of adoptive immunotherapy to treat/prevent BK nephropathy in kidney transplant recipients. She then pursued a post-doctoral fellowship with Dr. Megan Levings at the University of British Columbia on the use of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) regulatory T cells (Tregs) to induce transplant tolerance. Her lab is working on the development of adoptive immunotherapy in nephrology and understanding Treg dysfunction.

Dr. Tandon is an Associate Professor of Medicine, Co-Director of the Cirrhosis Care Clinic, Transplant Hepatologist and lead of the Cirrhosis Care Alberta quality improvement program. She obtained her training at the University of Alberta, the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona and Yale University. Her clinical practice and research are focused on cirrhosis with research interests including cirrhosis related complications, malnutrition, frailty, exercise therapy, palliative care, integrative health approaches such as meditation and knowledge translation. It is her career goal to provide wholistic, interdisciplinary, evidence based, patient-centered care through education, empowerment, engagement and team-work.

Dr. Tandon is an Associate Professor of Medicine, Co-Director of the Cirrhosis Care Clinic, Transplant Hepatologist and lead of the Cirrhosis Care Alberta quality improvement program. She obtained her training at the University of Alberta, the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona and Yale University. Her clinical practice and research are focused on cirrhosis with research interests including cirrhosis related complications, malnutrition, frailty, exercise therapy, palliative care, integrative health approaches such as meditation and knowledge translation. It is her career goal to provide wholistic, interdisciplinary, evidence based, patient-centered care through education, empowerment, engagement and team-work. Emily is a PhD student at the University of Alberta, where she completed her Master of Science (MSc) degree in medicine. With a passion for patient-oriented research and a commitment to improving health outcomes, Emily’s doctoral project focuses on EMPOWER, a 12-week online mind-body wellness program designed for adults living with chronic health conditions.

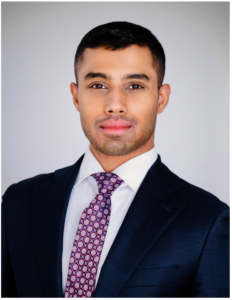

Emily is a PhD student at the University of Alberta, where she completed her Master of Science (MSc) degree in medicine. With a passion for patient-oriented research and a commitment to improving health outcomes, Emily’s doctoral project focuses on EMPOWER, a 12-week online mind-body wellness program designed for adults living with chronic health conditions. Dr Basil S. Nasir, M.B.B.Ch

Dr Basil S. Nasir, M.B.B.Ch Dr. Victor Ferreira is an Assistant Scientist in the Ajmera Transplant Centre at the University Health Network (UHN) and the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute (TGHRI). He is also an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology (LMP). He completed his PhD in Medical Sciences – Infection and Immunity Specialization at McMaster University in 2014 and post-doctoral training at UHN. His research program is focused on three pillars: I) using systems vaccinology to reveal insights into vaccine responses in immunocompromised individuals like transplant recipients; II) characterizing the impact of chronic viral infection on host immune responses; and III) developing novel methods for eliminating latent viruses in human organs. His work has been cited >2,500 times and is published in journals including the New England Journal of Medicine, Nature Immunology, the Lancet Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, the American Journal of Transplantation and Journal of Infectious Diseases.

Dr. Victor Ferreira is an Assistant Scientist in the Ajmera Transplant Centre at the University Health Network (UHN) and the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute (TGHRI). He is also an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology (LMP). He completed his PhD in Medical Sciences – Infection and Immunity Specialization at McMaster University in 2014 and post-doctoral training at UHN. His research program is focused on three pillars: I) using systems vaccinology to reveal insights into vaccine responses in immunocompromised individuals like transplant recipients; II) characterizing the impact of chronic viral infection on host immune responses; and III) developing novel methods for eliminating latent viruses in human organs. His work has been cited >2,500 times and is published in journals including the New England Journal of Medicine, Nature Immunology, the Lancet Infectious Diseases, Clinical Infectious Diseases, the American Journal of Transplantation and Journal of Infectious Diseases. Chemical Engineering as an Assistant Professor in August 2014. She is a biochemical engineer with expertise in bioprocess development, high‑throughput screening and stem cell culture optimization. Her research aims to develop bioprocesses to produce and transplant therapeutic cells to treat diabetes and cardiovascular disease. She notably developed new methods to encapsulate pancreatic islets, as well as vascular biomaterials surface modification strategies which are now applied by other researchers around the world. Her emerging leadership in bioengineering was recognized through the 2014 Martin Sinacore Outstanding Young Investigator Award from Engineering Conferences International & Biogen Idec, as well as the “Étoiles effervescence” award from Montreal InVivo.

Chemical Engineering as an Assistant Professor in August 2014. She is a biochemical engineer with expertise in bioprocess development, high‑throughput screening and stem cell culture optimization. Her research aims to develop bioprocesses to produce and transplant therapeutic cells to treat diabetes and cardiovascular disease. She notably developed new methods to encapsulate pancreatic islets, as well as vascular biomaterials surface modification strategies which are now applied by other researchers around the world. Her emerging leadership in bioengineering was recognized through the 2014 Martin Sinacore Outstanding Young Investigator Award from Engineering Conferences International & Biogen Idec, as well as the “Étoiles effervescence” award from Montreal InVivo.

Chantal Bémeur is a nutrition specialist in relation to liver disease and its many complications. Professor Bémeur trained as a dietitian/nutritionist and completed her graduate studies and two post-doctoral fellowships in nutrition, focusing on conditions affecting the hepatic and nervous systems, such as hepatic encephalopathy and Leigh Syndrome French Canadian. Professor Bémeur’s research activities are generally of a fundamental and clinical nature, including a collaboration with CHUM’s Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology. As an expert member of the International Society on Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism, Dr. Bémeur has participated in the development of guidelines on nutrition and liver disease. She is also part of a team of Canadian experts who developed an evidence-based nutritional education guide collaborating with people with chronic liver disease and their caregivers. She received an award from the Ordre professionnel des diététistes du Québec in 2018 for her work on this guide. Dr. Bémeur has published several book chapters, 30 scientific articles and over 100 scientific abstracts. Dr. Bémeur’s co-directs the HepatoNeuro Laboratory in the Cardiometabolic Axis of the Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CRCHUM). Several organizations, including the Donation and Transplantation Research Program of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research fund Dr. Bémeur’s research.

Chantal Bémeur is a nutrition specialist in relation to liver disease and its many complications. Professor Bémeur trained as a dietitian/nutritionist and completed her graduate studies and two post-doctoral fellowships in nutrition, focusing on conditions affecting the hepatic and nervous systems, such as hepatic encephalopathy and Leigh Syndrome French Canadian. Professor Bémeur’s research activities are generally of a fundamental and clinical nature, including a collaboration with CHUM’s Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology. As an expert member of the International Society on Hepatic Encephalopathy and Nitrogen Metabolism, Dr. Bémeur has participated in the development of guidelines on nutrition and liver disease. She is also part of a team of Canadian experts who developed an evidence-based nutritional education guide collaborating with people with chronic liver disease and their caregivers. She received an award from the Ordre professionnel des diététistes du Québec in 2018 for her work on this guide. Dr. Bémeur has published several book chapters, 30 scientific articles and over 100 scientific abstracts. Dr. Bémeur’s co-directs the HepatoNeuro Laboratory in the Cardiometabolic Axis of the Centre de recherche du Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CRCHUM). Several organizations, including the Donation and Transplantation Research Program of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research fund Dr. Bémeur’s research.

Dr Thozama Siyotula is a distinguished paediatric surgeon at Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. With a profound interest in hepatobiliary, transplant, thoracic and neonatal surgical outcomes. She completed her undergraduate training in 2011 at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Furthering her studies she went on to specialise in paediatric surgery through the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa, completing her FCPaedSurg (SA) in 2021 and a master’s in medicine (Paediatric Surgery) in 2021 at the University of Cape Town. She currently works as a paediatric surgeon and transplant surgeon. A senior lecture at the University of Cape Town and course convenor for the 5th year undergraduate paediatric surgery program at the University of Cape Town.

Dr Thozama Siyotula is a distinguished paediatric surgeon at Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in Cape Town, South Africa. With a profound interest in hepatobiliary, transplant, thoracic and neonatal surgical outcomes. She completed her undergraduate training in 2011 at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Furthering her studies she went on to specialise in paediatric surgery through the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa, completing her FCPaedSurg (SA) in 2021 and a master’s in medicine (Paediatric Surgery) in 2021 at the University of Cape Town. She currently works as a paediatric surgeon and transplant surgeon. A senior lecture at the University of Cape Town and course convenor for the 5th year undergraduate paediatric surgery program at the University of Cape Town. David Thomson is a critical care subspecialist and abdominal transplant surgeon at Groote Schuur Hospital and the University of Cape Town. His interests are deceased donation, ECMO, medical education and system improvement. He created the massive open online course Organ Donation: From Death to Life hosted on Coursera.org to improve education around organ donation and transplantation. He is the immediate past President of the Southern African Transplantation Society and led development on a report on Organ and Tissue Donation in South Africa: Creating a National Strategic Roadmap in collaboration with the International Society for Organ Donation and Procurement. He worked on the World Brain Death Project and is the lead author on the South African Guidelines for Determination of Death published in 2021.

David Thomson is a critical care subspecialist and abdominal transplant surgeon at Groote Schuur Hospital and the University of Cape Town. His interests are deceased donation, ECMO, medical education and system improvement. He created the massive open online course Organ Donation: From Death to Life hosted on Coursera.org to improve education around organ donation and transplantation. He is the immediate past President of the Southern African Transplantation Society and led development on a report on Organ and Tissue Donation in South Africa: Creating a National Strategic Roadmap in collaboration with the International Society for Organ Donation and Procurement. He worked on the World Brain Death Project and is the lead author on the South African Guidelines for Determination of Death published in 2021.

About Dr. Julie Ho

About Dr. Julie Ho Dr. Tom Blydt-Hansen completed his MD at McGill University, and his Pediatric and Nephrology specialization at the Montreal Children’s Hospital, followed by further specialization in transplantation at the University of California, Los Angeles. He began his Nephrology career at the University of Manitoba in 2001, where he was Division Head of Nephrology from 2005-2014.

Dr. Tom Blydt-Hansen completed his MD at McGill University, and his Pediatric and Nephrology specialization at the Montreal Children’s Hospital, followed by further specialization in transplantation at the University of California, Los Angeles. He began his Nephrology career at the University of Manitoba in 2001, where he was Division Head of Nephrology from 2005-2014. Monica Bronowski completed an undergraduate degree in neuroscience at Dalhousie University, with a focus on innovative neurotechnology. Before starting her PhD, she worked in hematology, oncology, and bone marrow transplant (BMT), conducting clinical trials across various study phases for multiple myeloma, bone marrow transplant, and CAR-T therapies. This experience exposed her to both early and late-phase clinical trials, deepening her interest in translational research.

Monica Bronowski completed an undergraduate degree in neuroscience at Dalhousie University, with a focus on innovative neurotechnology. Before starting her PhD, she worked in hematology, oncology, and bone marrow transplant (BMT), conducting clinical trials across various study phases for multiple myeloma, bone marrow transplant, and CAR-T therapies. This experience exposed her to both early and late-phase clinical trials, deepening her interest in translational research. Angela Hamie has just graduated from the University of Alberta and holds a Bachelor of Science with Honors in Immunology and Infection. Her presentation will summarize her research conducted throughout her fourth year undergraduate thesis project, which focuses on the Age, Thymus Excision, Organ Type, and Immunosuppression on Lymphocyte Subpopulations in pediatric transplantation.

Angela Hamie has just graduated from the University of Alberta and holds a Bachelor of Science with Honors in Immunology and Infection. Her presentation will summarize her research conducted throughout her fourth year undergraduate thesis project, which focuses on the Age, Thymus Excision, Organ Type, and Immunosuppression on Lymphocyte Subpopulations in pediatric transplantation. Mitchell Wagner is currently a first year medical student at the University of Alberta. He graduated from the U of A in 2022 with an Honors degree in Immunology and Infection with a certificate in biomedical research. He recently defended a Master of Science in Experimental Surgery, focusing on the optimization of out-of-body heart perfusion. Mitchell’s main research interest is on strategies that improve donated organs through ex-situ heart perfusion apparati, however has also been involved in clinical research within the areas of radiology, respiratory medicine, and cardiology. Mitchell is the recipient of multiple prestigious awards such as the Canada Graduate Scholarship – Masters and the Cote Biomedical Research Studentship. As an aspiring surgeon-scientist, he intends on completing an MD/PhD program focusing to further improve out of body heart perfusion protocols.

Mitchell Wagner is currently a first year medical student at the University of Alberta. He graduated from the U of A in 2022 with an Honors degree in Immunology and Infection with a certificate in biomedical research. He recently defended a Master of Science in Experimental Surgery, focusing on the optimization of out-of-body heart perfusion. Mitchell’s main research interest is on strategies that improve donated organs through ex-situ heart perfusion apparati, however has also been involved in clinical research within the areas of radiology, respiratory medicine, and cardiology. Mitchell is the recipient of multiple prestigious awards such as the Canada Graduate Scholarship – Masters and the Cote Biomedical Research Studentship. As an aspiring surgeon-scientist, he intends on completing an MD/PhD program focusing to further improve out of body heart perfusion protocols. Sarjana Alam is an undergraduate science student at the University of Alberta, where she is a research trainee under the supervision of Dr. Esme Dijke in the Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology. She is involved in a project investigating the cryopreservation of T regulatory cells for tolerogenic cell therapy.

Sarjana Alam is an undergraduate science student at the University of Alberta, where she is a research trainee under the supervision of Dr. Esme Dijke in the Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology. She is involved in a project investigating the cryopreservation of T regulatory cells for tolerogenic cell therapy. Marie-Pier joined Dre. Marie-Josée Hébert’s lab in the nephrology, transplantation and renal regeneration research unit at the CRCHUM in 2024. She obtained her BSc degree in biology at McGill university and is now pursuing a Masters degree in the Molecular Biology program at l’Université de Montréal. She is currently working on evaluating the pro-angiogenic potential of RNAs enriched in apoptotic exosomes and whether these RNAs cooperate to modulate endothelial function. Marie-Pier is also a trainee in the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research program (CDTRP).Outside of the lab, Marie-Pier loves to read, go to spin classes and play word games like Scattegories and Bananagrams.

Marie-Pier joined Dre. Marie-Josée Hébert’s lab in the nephrology, transplantation and renal regeneration research unit at the CRCHUM in 2024. She obtained her BSc degree in biology at McGill university and is now pursuing a Masters degree in the Molecular Biology program at l’Université de Montréal. She is currently working on evaluating the pro-angiogenic potential of RNAs enriched in apoptotic exosomes and whether these RNAs cooperate to modulate endothelial function. Marie-Pier is also a trainee in the Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research program (CDTRP).Outside of the lab, Marie-Pier loves to read, go to spin classes and play word games like Scattegories and Bananagrams. Dr. Andreas Kramer is a Clinical Associate Professor in the Departments of Critical Care Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences. He graduated from medical school at the University of Manitoba in 1997 and received specialty training in internal medicine and critical care at the University of Calgary in 2002. After working for three years as a community internist and intensivist in Manitoba, he obtained fellowship training in neurocritical care at the University of Virginia 2005-2007. During this time, he also completed a Master of Science degree in Health Evaluation Sciences. Dr. Kramer joined the Department of Critical Care Medicine in Calgary in 2007. He has a particular research and clinical interest in neuro-monitoring and prevention of secondary brain injury in neurocritical care patients. Dr. Kramer is on the Editorial Boards of the journals Neurocritical Care and Critical Care Medicine. He has over 90 peer-reviewed publications, with about half of these as first or senior author. He is a co-investigator in a number of CIHR-sponsored clinical trials. Dr. Kramer has written multiple textbook chapters on a variety of neurocritical care topics, and was the co-editor of two 2017 neurocritical care editions of the Handbook in Clinical Neurology. Since 2011, he has been the Medical Director of the Southern Alberta Organ and Tissue Donation Program, and serves on numerous Canadian Blood Services advisory committees. Dr. Kramer is married with four very energetic children between the ages of 9 and 17.

Dr. Andreas Kramer is a Clinical Associate Professor in the Departments of Critical Care Medicine and Clinical Neurosciences. He graduated from medical school at the University of Manitoba in 1997 and received specialty training in internal medicine and critical care at the University of Calgary in 2002. After working for three years as a community internist and intensivist in Manitoba, he obtained fellowship training in neurocritical care at the University of Virginia 2005-2007. During this time, he also completed a Master of Science degree in Health Evaluation Sciences. Dr. Kramer joined the Department of Critical Care Medicine in Calgary in 2007. He has a particular research and clinical interest in neuro-monitoring and prevention of secondary brain injury in neurocritical care patients. Dr. Kramer is on the Editorial Boards of the journals Neurocritical Care and Critical Care Medicine. He has over 90 peer-reviewed publications, with about half of these as first or senior author. He is a co-investigator in a number of CIHR-sponsored clinical trials. Dr. Kramer has written multiple textbook chapters on a variety of neurocritical care topics, and was the co-editor of two 2017 neurocritical care editions of the Handbook in Clinical Neurology. Since 2011, he has been the Medical Director of the Southern Alberta Organ and Tissue Donation Program, and serves on numerous Canadian Blood Services advisory committees. Dr. Kramer is married with four very energetic children between the ages of 9 and 17. Dr. Mypinder Sekhon is an intensivist and clinician-scientist in the intensive care unit at Vancouver General Hospital. He completed his medical school training, internal medicine residency and critical care medicine subspecialty fellowship at the University of British Columbia prior to completing a neurocritical care fellowship at Addenbrooke’s Hospital at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom under the guidance of Professors David Menon and Arun Gupta. Subsequently, he completed is PhD in neurovascular sciences under Professor Philip Ainslie, a Canada Research Chair in cerebrovascular physiology. His clinical and research interests include multimodal neuromonitoring, cerebral autoregulation disturbance after brain injury and critical care management of severe acute brain injury patients.

Dr. Mypinder Sekhon is an intensivist and clinician-scientist in the intensive care unit at Vancouver General Hospital. He completed his medical school training, internal medicine residency and critical care medicine subspecialty fellowship at the University of British Columbia prior to completing a neurocritical care fellowship at Addenbrooke’s Hospital at the University of Cambridge, United Kingdom under the guidance of Professors David Menon and Arun Gupta. Subsequently, he completed is PhD in neurovascular sciences under Professor Philip Ainslie, a Canada Research Chair in cerebrovascular physiology. His clinical and research interests include multimodal neuromonitoring, cerebral autoregulation disturbance after brain injury and critical care management of severe acute brain injury patients. My name is Matthew Kolisnyk. I am a third-year PhD Candidate in Neuroscience at Western University. My undergraduate training was in Psychology and Statistics, where I spent time applying neuroimaging techniques to memory and mindfulness research. In my current lab, I use neuroimaging to measure residual cognitive function in patients who have sustained an acute brain injury and use that neural measure in combination with machine learning to try and predict which patients will survive their injury. I currently am a research associate at the London Health Science Centre, where we measure physiological and neural changes that occur when patients undergo planned withdrawal of life-sustaining measures.

My name is Matthew Kolisnyk. I am a third-year PhD Candidate in Neuroscience at Western University. My undergraduate training was in Psychology and Statistics, where I spent time applying neuroimaging techniques to memory and mindfulness research. In my current lab, I use neuroimaging to measure residual cognitive function in patients who have sustained an acute brain injury and use that neural measure in combination with machine learning to try and predict which patients will survive their injury. I currently am a research associate at the London Health Science Centre, where we measure physiological and neural changes that occur when patients undergo planned withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. Jordan is a PhD student at UBC working in the Vancouver General Hospital ICU. His current work focuses on donation after circulatory death by looking at how the brain responds during the dying process after withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. During Jordan’s undergraduate degree in Health Sciences and Physics, he got his start in research focusing on whole body hypoxia in the context of high altitude physiology. This led to working in industry since 2020 using medical imaging to evaluate hypoxia and ischemia in wound care, vascular surgery, and plastic and reconstructive surgery. Jordan returned to school in 2021 to pursue a MSc with Dr. Glen Foster at UBCO focusing on developing and validating a new medical imaging approach to quantify diaphragm blood flow in humans. In 2023, Jordan joined the ICU Research Group to continue looking at oxygenation and blood flow in critically ill patients. As such, the unifying theme of Jordan’s work involves investigating low oxygen and blood flow in both healthy and clinical populations. This focus on physiology underpins the organ procurement process in donation after circulatory death as warm ischemic times may render organs ineligible for transplantation. Outside of research, Jordan can be found playing hockey, biking, running, reading, or trying to spend as much time outdoors in Alberta or British Columbia.

Jordan is a PhD student at UBC working in the Vancouver General Hospital ICU. His current work focuses on donation after circulatory death by looking at how the brain responds during the dying process after withdrawal of life-sustaining measures. During Jordan’s undergraduate degree in Health Sciences and Physics, he got his start in research focusing on whole body hypoxia in the context of high altitude physiology. This led to working in industry since 2020 using medical imaging to evaluate hypoxia and ischemia in wound care, vascular surgery, and plastic and reconstructive surgery. Jordan returned to school in 2021 to pursue a MSc with Dr. Glen Foster at UBCO focusing on developing and validating a new medical imaging approach to quantify diaphragm blood flow in humans. In 2023, Jordan joined the ICU Research Group to continue looking at oxygenation and blood flow in critically ill patients. As such, the unifying theme of Jordan’s work involves investigating low oxygen and blood flow in both healthy and clinical populations. This focus on physiology underpins the organ procurement process in donation after circulatory death as warm ischemic times may render organs ineligible for transplantation. Outside of research, Jordan can be found playing hockey, biking, running, reading, or trying to spend as much time outdoors in Alberta or British Columbia. Hayden John is a student researcher passionate about addressing health inequities through patient and community-centred research. He has recently completed the Queen’s Accelerated Route to Medical School (QuARMS) pathway and is a first-year medical student at Queen’s University. Currently, he is a research student with the Kidney Health Education Research Group (KHERG) focusing on the A.C.TI.O.N Project: Improving Access to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation (LDKT) in Ethno-racial Minority Communities in Canada. Under the supervision of Principal Investigator Dr. Istvan Mucsi, Hayden explored the perceived risks and benefits of kidney donation among African, Caribbean and Black Canadians.

Hayden John is a student researcher passionate about addressing health inequities through patient and community-centred research. He has recently completed the Queen’s Accelerated Route to Medical School (QuARMS) pathway and is a first-year medical student at Queen’s University. Currently, he is a research student with the Kidney Health Education Research Group (KHERG) focusing on the A.C.TI.O.N Project: Improving Access to Living Donor Kidney Transplantation (LDKT) in Ethno-racial Minority Communities in Canada. Under the supervision of Principal Investigator Dr. Istvan Mucsi, Hayden explored the perceived risks and benefits of kidney donation among African, Caribbean and Black Canadians. Meghan He is a UBC medical student who studied Comparative Literature and Psychobiology at UCLA. Her research focuses on grounding medicine in the humanity of patient stories. She is co-President of the UBC Surgical Club, where she co-founded the EDI advocacy group, UpSurge, in alliance in the UBC Department of Surgery. In her free time, she teaches kids’ yoga with the Vancouver School Board and volunteers for community dance events.

Meghan He is a UBC medical student who studied Comparative Literature and Psychobiology at UCLA. Her research focuses on grounding medicine in the humanity of patient stories. She is co-President of the UBC Surgical Club, where she co-founded the EDI advocacy group, UpSurge, in alliance in the UBC Department of Surgery. In her free time, she teaches kids’ yoga with the Vancouver School Board and volunteers for community dance events.

Dr. David Nicholas is a Professor and Associate Dean, Research and Partnerships in the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Calgary. He is the author of over 200 peer-reviewed research publications addressing topics such as wellbeing and transition to adulthood in chronic health conditions, including kidney disease. Dr. Nicholas’ research further focuses on capacity development in service delivery as well as navigation support for individuals with chronic health issues and disability, and their families. Dr. Nicholas has been the principal investigator on multiple grants from provincial, federal and international sources. He also brings clinical experience as a former nephrology social worker.

Dr. David Nicholas is a Professor and Associate Dean, Research and Partnerships in the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Calgary. He is the author of over 200 peer-reviewed research publications addressing topics such as wellbeing and transition to adulthood in chronic health conditions, including kidney disease. Dr. Nicholas’ research further focuses on capacity development in service delivery as well as navigation support for individuals with chronic health issues and disability, and their families. Dr. Nicholas has been the principal investigator on multiple grants from provincial, federal and international sources. He also brings clinical experience as a former nephrology social worker.

Sarah Pol is a Clinical Research Project Manager in the Anthony Lab at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). She completed her undergraduate training in Health Sciences, Anthropology and Community Development at Western University, received a Master of Science in Global Health from McMaster University and pursued further training in Project Management at the University of Toronto. She is the User Experience and Implementation Lead for Voxe, an innovative, child- and healthcare provider-friendly, electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROM) platform for data capture and visualization. She is intricately involved in the SickKids Mental Health Measurement-Based Care (MBC) initiative’s clinical implementation of Voxe. Sarah is passionate about equity-oriented health research, the use of qualitative methods to amplify patients’ voices, artificial intelligence, and the meaningful integration of ePROMs into clinical practice to support MBC.

Sarah Pol is a Clinical Research Project Manager in the Anthony Lab at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids). She completed her undergraduate training in Health Sciences, Anthropology and Community Development at Western University, received a Master of Science in Global Health from McMaster University and pursued further training in Project Management at the University of Toronto. She is the User Experience and Implementation Lead for Voxe, an innovative, child- and healthcare provider-friendly, electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROM) platform for data capture and visualization. She is intricately involved in the SickKids Mental Health Measurement-Based Care (MBC) initiative’s clinical implementation of Voxe. Sarah is passionate about equity-oriented health research, the use of qualitative methods to amplify patients’ voices, artificial intelligence, and the meaningful integration of ePROMs into clinical practice to support MBC. Jia Lin, MPH, is a Clinical Research Project Coordinator working alongside Dr. Samantha Anthony, a Health Clinician Scientist, in the Child Health Evaluative Sciences program at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. The Anthony Lab examines the biopsychosocial impact of pediatric chronic illness on patients and families, with a focus on patient engagement, patient-reported outcome measures, implementation science, and mixed methods. In her role, Jia leads multiple clinical research studies across the research pipeline, including a current multi-phase, cross-Canada study exploring the experiences of Indigenous children and families who have received a solid organ transplantation. Rooted in patient and community engagement, this research employs storytelling to consider the multiplicity of knowledge, including Indigenous Knowledge, to advance child health equity. Jia recently began her PhD at McGill University with research interests at the nexus of equity-oriented, patient-engaged health research and applying critical qualitative approaches to amplify patients’ voices.

Jia Lin, MPH, is a Clinical Research Project Coordinator working alongside Dr. Samantha Anthony, a Health Clinician Scientist, in the Child Health Evaluative Sciences program at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. The Anthony Lab examines the biopsychosocial impact of pediatric chronic illness on patients and families, with a focus on patient engagement, patient-reported outcome measures, implementation science, and mixed methods. In her role, Jia leads multiple clinical research studies across the research pipeline, including a current multi-phase, cross-Canada study exploring the experiences of Indigenous children and families who have received a solid organ transplantation. Rooted in patient and community engagement, this research employs storytelling to consider the multiplicity of knowledge, including Indigenous Knowledge, to advance child health equity. Jia recently began her PhD at McGill University with research interests at the nexus of equity-oriented, patient-engaged health research and applying critical qualitative approaches to amplify patients’ voices.

I obtained my PharmD from the University of Montreal, where I developed a strong foundation in pharmacotherapy. Eager to deepen my expertise, I completed a master’s in advanced pharmacotherapy, which enabled me to become a hospital pharmacist. For several years, I specialized as a cardiology and heart failure pharmacist, gaining invaluable experience in managing complex patient needs. Driven by a desire to expand my clinical skills, I pursued a medical degree, graduating with my MD from the University of Montreal in 2021 and earning a place on the Dean’s List. Following this achievement, I completed my training in internal medicine, and as of July 2024, I am currently in a cardiology residency at the University of Montreal. My primary interests lie in advanced heart failure and heart transplantation, areas in which I am actively involved in research with the advanced heart failure and heart transplant team at the Montreal Heart Institute. My background in pharmacy and medicine uniquely positions me to contribute to the evolving field of heart transplantation.

I obtained my PharmD from the University of Montreal, where I developed a strong foundation in pharmacotherapy. Eager to deepen my expertise, I completed a master’s in advanced pharmacotherapy, which enabled me to become a hospital pharmacist. For several years, I specialized as a cardiology and heart failure pharmacist, gaining invaluable experience in managing complex patient needs. Driven by a desire to expand my clinical skills, I pursued a medical degree, graduating with my MD from the University of Montreal in 2021 and earning a place on the Dean’s List. Following this achievement, I completed my training in internal medicine, and as of July 2024, I am currently in a cardiology residency at the University of Montreal. My primary interests lie in advanced heart failure and heart transplantation, areas in which I am actively involved in research with the advanced heart failure and heart transplant team at the Montreal Heart Institute. My background in pharmacy and medicine uniquely positions me to contribute to the evolving field of heart transplantation. Ikram Abow-Mohamed is a PGY-3 Internal Medicine resident at McGill University, set to begin a Gastroenterology fellowship at McGill in the upcoming year.

Ikram Abow-Mohamed is a PGY-3 Internal Medicine resident at McGill University, set to begin a Gastroenterology fellowship at McGill in the upcoming year. Eva Amzallag holds a master’s degree in anthropology (2018) and a master’s degree in epidemiology (2024), both from Université de Montréal. Currently pursuing a PhD in epidemiology, her research interests include liver transplantation, transfusional medicine, and postoperative complications. Under the supervision of Dr. François Martin Carrier, anesthesiologist at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and CDTRP Investigator, her work explores the relationship between blood transfusions and postoperative pulmonary complications in liver transplant recipients.

Eva Amzallag holds a master’s degree in anthropology (2018) and a master’s degree in epidemiology (2024), both from Université de Montréal. Currently pursuing a PhD in epidemiology, her research interests include liver transplantation, transfusional medicine, and postoperative complications. Under the supervision of Dr. François Martin Carrier, anesthesiologist at the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal and CDTRP Investigator, her work explores the relationship between blood transfusions and postoperative pulmonary complications in liver transplant recipients. Vanessa is a PhD-nurse, and a former Organ Donation Coordinator who has been devoted to research and active involvement in Organ Donation and Transplantation activities for over 10 years. Her research expertise is focused in quality improvement of organ donation programs and structures worldwide. She was a Kidney Research Scientist Core Education Program (KRESCENT) fellow and a Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program (CDTRP) trainee. She currently co-leads two groups within the CDTRP structure: Theme 1 “Improve the Culture of Donation” and the Allied Research in Donation and Transplantation (ARDOT) working group. She is currently an Assistant Professor at Brock University, and lead the investigation of burnout among donation coordinators, with the support and collaboration of Canadian Blood Services and key organ donation researchers nationally and internationally.

Vanessa is a PhD-nurse, and a former Organ Donation Coordinator who has been devoted to research and active involvement in Organ Donation and Transplantation activities for over 10 years. Her research expertise is focused in quality improvement of organ donation programs and structures worldwide. She was a Kidney Research Scientist Core Education Program (KRESCENT) fellow and a Canadian Donation and Transplantation Research Program (CDTRP) trainee. She currently co-leads two groups within the CDTRP structure: Theme 1 “Improve the Culture of Donation” and the Allied Research in Donation and Transplantation (ARDOT) working group. She is currently an Assistant Professor at Brock University, and lead the investigation of burnout among donation coordinators, with the support and collaboration of Canadian Blood Services and key organ donation researchers nationally and internationally. Dr. Somaya Zahran is currently a Nephrology fellow at McGill University and serves as a Chief fellow in the program. She earned her medical degree from Egypt and completed her PhD at the University of Alberta before pursuing internal medicine residency and nephrology fellowship at McGill University. Dr. Zahran is an AJKD editorial intern and a trainee member of the Canadian Society of Nephrology Clinical Practice Guideline Committee. She is looking forward to starting her Transplant fellowship at Mayo Clinic, Rochester in Jul 2025. Outside of her academic pursuits, Somaya loves spending time with her family and getting creative in the kitchen—she’s on a mission to find the perfect balance between kidney health and decadent desserts!

Dr. Somaya Zahran is currently a Nephrology fellow at McGill University and serves as a Chief fellow in the program. She earned her medical degree from Egypt and completed her PhD at the University of Alberta before pursuing internal medicine residency and nephrology fellowship at McGill University. Dr. Zahran is an AJKD editorial intern and a trainee member of the Canadian Society of Nephrology Clinical Practice Guideline Committee. She is looking forward to starting her Transplant fellowship at Mayo Clinic, Rochester in Jul 2025. Outside of her academic pursuits, Somaya loves spending time with her family and getting creative in the kitchen—she’s on a mission to find the perfect balance between kidney health and decadent desserts!